History to chew on

July 3, 2014 by Jane When people think

of Vietnamese food, one of the first things that comes to mind is

banh mi. While many people love these sandwiches, they may

only know a smidgen of the history behind them. Lucky for us, Andrea Nguyen

knows the fascinating history of the sandwich that inspired her

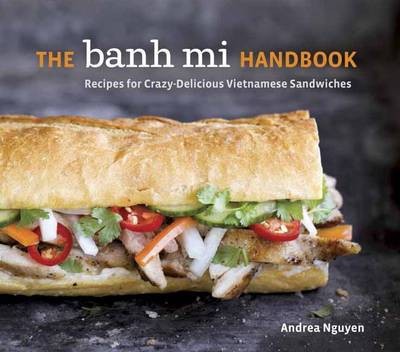

latest cookbook, The Banh Mi

Handbook. (You can enter our contest for your chance to win one of

three copies.) We asked Andrea to share her knowledge of banh

mi, and she generously obliged:

When people think

of Vietnamese food, one of the first things that comes to mind is

banh mi. While many people love these sandwiches, they may

only know a smidgen of the history behind them. Lucky for us, Andrea Nguyen

knows the fascinating history of the sandwich that inspired her

latest cookbook, The Banh Mi

Handbook. (You can enter our contest for your chance to win one of

three copies.) We asked Andrea to share her knowledge of banh

mi, and she generously obliged:

“Isn’t Vietnamese food heavily influenced by French ideas?” is a question I’m often asked. Sort of… but in fact, the French were in Vietnam for only a portion of its history. They officially ruled Vietnam from 1883 to 1954 but arrived as early as the seventeenth century. Yes, French colonials introduced baguettes to Vietnam, and somehow, plucky local cooks managed to bake crisp, lofty bread in the tropical heat. Look deeper into Viet history, however, and you’ll realize that the Chinese ruled Vietnam on and off for a total of about 1,000 years. Their presence is very strong in Vietnamese food – which is at core an unusual amalgam of East and West.

Banh mi, the signature Vietnamese sandwich, offers a great lens for exploring Vietnamese history and culture. Each bite represents a multitude of cultural mash-ups. The bread, condiments, and some of the meats are the legacy of Chinese and French colonialism. The pickles, cilantro, and chile reflect Viet tastes for bright flavors and fresh vegetables.

When the French first introduced baguettes, the Viets called the bread banh Tay (western or French bread; banh is a generic term for foods made with flours and legumes). It was mainly associated with French foods such as bo, pho-mat, and bit-tet – Vietnamese pidgin terms for French beurre (butter), fromage (cheese), and bifteck (beef steaks). By 1945, the bread had become commonplace enough for its name to switch to banh mi, literally meaning bread made from wheat (mi). Dropping the Tay signaled that the bread had been fully accepted as a Viet food. The French brought baguettes to Vietnam and the Vietnamese liked it well enough to make it their own.

People like my parents, born in 1930s northern Vietnam, snacked on freshly baked, fist-shaped rolls simply adorned with salt and pepper. Most of the sandwiches made in northern Vietnam at that time were simple affairs, just bread, meat and seasonings, without any vegetable additions. That purity contrasted with the action in the south, particularly in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City), where cooks were concocting fanciful renditions, reflections of their freewheeling attitude and living-large lifestyle.

Around the

early 1940s, Saigon vendors started offering an East-meets-West

combination of cold cuts stuffed inside baguette with canned French

butter or fresh mayonnaise, pickles, cucumber, cilantro, and chile.

Maggi Seasoning sauce, a soy sauce-like condiment likely introduced

by the French, was the condiment of choice for adding savory depth.

Somewhere along the line, the term banh mi came to signal

not only bread but the ubiquitous sandwich.

Around the

early 1940s, Saigon vendors started offering an East-meets-West

combination of cold cuts stuffed inside baguette with canned French

butter or fresh mayonnaise, pickles, cucumber, cilantro, and chile.

Maggi Seasoning sauce, a soy sauce-like condiment likely introduced

by the French, was the condiment of choice for adding savory depth.

Somewhere along the line, the term banh mi came to signal

not only bread but the ubiquitous sandwich.

Reunification of North and South Vietnam via the communist takeover in 1975 resulted in a mass exodus of refugees to America, Australia, France and elsewhere. Those who came from Saigon and the surrounding areas brought fond memories of Saigon-style sandwiches and yearned to savor them once more. Banh mi shops, bakeries, and delis sprung up in response. What most people think of as banh mi has roots in the Saigon-style sandwich.

Nowadays, the customizable, affordable sandwich is known far beyond the borders of Little Saigon neighborhoods. Modern banh mi shops like Baoguette in New York, Baguette Box in Seattle, Bun Mee in San Francisco, and Saigon Sisters in Chicago crank out sandwiches for downtown professionals and hipsters alike. Banh mi food trucks, the modern version of Vietnam’s itinerant banh mi street vendors, attract legions of hungry fans. Meanwhile, mini chains of Viet-American delis, as well as mom-and-pop sandwich shops in Little Saigons all over are jumping with business.

Banh mi recipes are showing up in cookbooks, newspapers, magazines, and food television shows. Online chatter about banh mi is plentiful too. Yum(!) Brands, the parent company of Kentucky Fried Chicken, Taco Bell, and Pizza Hut, is launching an experimental banh mi endeavor called Banh Shop.

So while you’re enjoying banh mi, you’re savoring Vietnamese food history, participating in global food culture, and heck, eating a super tasty sandwich.

Andrea Nguyen is the author of The Banh Mi Handbook (Ten Speed Press). Keep up with her at Vietworldkitchen.com.

Categories

- All Posts (6940)

- Antipasto (2135)

- Author Articles (247)

- Book News (935)

- Cookbook Giveaways (983)

- Cookbook Lovers (257)

- Cooking Tips (109)

- Culinary News (299)

- Food Biz People (552)

- Food Online (791)

- Holidays & Celebrations (272)

- New Cookbooks (149)

- Recipes (1500)

- Shelf Life With Susie (231)

- What's New on EYB (133)

Archives

Latest Comments

- eliza on What foods do you look forward to the most for each season?

- kmwyman on Rooza by Nadiya Hussain – Cookbook Review and Giveaway

- Maryd8822 on The Golden Wok – Cookbook Giveaway

- Dendav on Danube Cookbook Review and Giveaway

- sanfrannative on Rooza by Nadiya Hussain – Cookbook Review and Giveaway

- darty on Danube Cookbook Review and Giveaway

- Atroyer7 on Danube Cookbook Review and Giveaway

- demomcook on What foods do you look forward to the most for each season?

- demomcook on Danube Cookbook Review and Giveaway

- Darcie on How cookbooks can help build resilience