How to brine turkey and make gravy from a flavor scientist

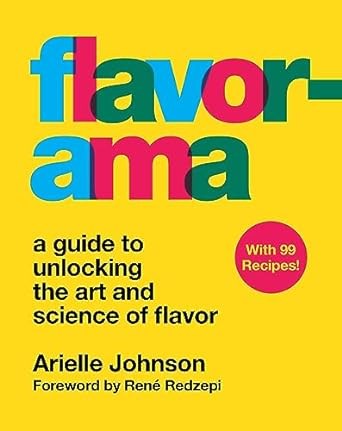

November 17, 2023 by JennyHere in the US, most cooks are planning their Thanksgiving day meals and to help a bit with that task, we have an excerpt from a book that will be released in March of 2024. Flavorama: The Unbridled Science of Flavor and How to Get It to Work for You by Arielle Johnson delivers recipes designed to easily finesse flavor to give any dish a little oomph, easily swap out an ingredient for one you have on hand, use a recipe or technique to improvise something new, or boldly replicate a flavor.

I did a quick review of the galley and it looks spectacular. It is a true cookery course that dives deep into the hows and whys of all things flavor with countless illustrations and tables to visually bring the science and facts to life.

Arielle Johnson is a flavor scientist who advises some of the top chefs, restaurants, and bars in the world. She received her Ph.D. from UC Davis; cofounded the fermentation lab at the restaurant Noma in Copenhagen; served as the science officer for Alton Brown’s beloved television show Good Eats; and was a director’s fellow at the MIT Media Lab. Named by the World’s 50 Best Restaurants as one of the people shaping the future of gastronomy, she has lectured on food and science at SXSW, Tales of the Cocktail, WIRED, and the Harvard Science and Cooking Lecture Series, and her writing on the subject has appeared in the Los Angeles Times and Lucky Peach. She lives in New York City and currently serves as Science Director of Noma Projects and co-founder of Retronasal Industries.

Brine Without the Brine: Dry-Salting

Gastronomic chatter around brining tends to peak around Thanksgiving, when you’ll see exhortations and procedures for submerging your turkey in salty water for a few days before you plan to roast it. But a cold soak in a 5 to 8 percent salt brine is also touted for chicken, pork chops, and other more everyday cuts of meat. The endgame? Thoroughly and evenly salty flavor, for one. The other benefits have less to do with tastes and rely on the significant changes salt can make to the texture of proteins.

Meat is a muscle, and a muscle is basically a striated sponge, made from incrementally layered and twisted fibrous proteins, and soaked in juices. Most muscle proteins just sit next to water, rather than dissolving in it (like mixing pieces of boiled egg with water, instead of a raw liquid egg).

Facilitated by salt, a few of these proteins can dissolve into the juices of the muscle like melting gelatin, leaving a loosened solid matrix behind, and creating a juicy, binding effect. (This is easiest to see in sausages, which, when well-salted, have a bouncy, cohesive texture rather than a crumbly one.)

Proteins are all long strands of amino acids, each of which has unique stick-outty bits that act kind of like different types of fasteners: magnets, hooks, Velcro. A protein achieves, and holds, its particular globular or fibrous shape when it crumples up, and these different genres of fasteners catch on their matching mates. Speaking more literally, many of these amino acids carry ionic charges as part of their shape-holding mechanism, and when salt ions slowly diffuse into the muscle, they mess around with those charges a bit. Now, the protein strands repel and push away from one another, like strands of your hair ionically charged with static electricity. Since those proteins are interconnected in the muscle, it’s kind of like your diaphragm pushing down and away from your chest cavity when you breathe. Instead of pulling in air, the proteins pull in the watery juices they’re bathed in, and hold on to them. In real terms, it means a noticeably juicier piece of meat.

With its big containers and overnight soaking in quarts of liquid, brining can feel like a production. But you can still get some of the benefits of salt and osmosis by generously salting meaty ingredients and keeping them in the fridge for a day or so before you cook them. Whole chickens or skin-on chicken parts, steaks, pork loins or chops, and turkeys all become juicier, from the same protein-juice push-pull as brining, when given a salty rubdown and rest. (And, of course, seasoned into their bulk, rather than just on the surface.) Salt these generously – think confident, seasoning sprinkle rather than a whole-handed toss of salt – sit them on a plate in the fridge, and let the salt diffuse in for 4 to 6 hours or for up to 24 hours, when the process may begin to dry out the meat and make it disagreeably salty.

Deglazing, Extraction, and Pan Sauces. Plus, a Supposedly Dumb Thing I’ll Definitely Do Again

You’re cooking a piece of meat (which, as we know from page 185, is a network of mostly unflavored proteins soaked in water full of lightly flavored molecules and flavor precursors – yum – that create meaty flavor when you heat them). As you bake, roast, sear, or sauté, the just-add-heat-to-create-meat-flavor juices leak out. As the protein heats and starts tasting meaty, then starts browning, a thin layer of browned-meat juice builds up on the meat and in the pan. (For more on how browning happens and creates flavors, see page 244.) When you’re finished, you have a flavorful sear on the meat, and a corresponding cooked-on layer, which a French-trained cook would call a fond, stuck to the pan.

Your first thought might be to scrub it off, but if you do wash it down the drain, you’ll be missing out on one of the most delicious meaty-flavor substances you can make, as a free by-product of something you’re already doing. All you have to do is collect it. For that, we have a technique called deglazing, which is really just making an extraction with a hot, water-based liquid. Deglazing can be as simple as splashing half a cup of wine in the emptied pan and letting it bubble up, dissolve, and extract the cooked- on components as it boils, scraping a little to loosen any stuck parts. (Then, pouring it over your meat, or on any vegetables you eat with it.)

Extraction by deglazing is easy to turn into a pan sauce: use stock, heavy cream, crème fraîche, apple cider or cherry juice, or flavorful vinegar to dissolve the fond. Maybe throw in a pinch of cracked black pepper, cumin, or coriander seeds to infuse your liquid as it bubbles, then fish them out. Gently cook until it’s a thickness you find appealing, then remove from the heat and whisk in some mustard or citrus juice, fresh minced herbs, or capers as your heart desires.

Traditional gravy is basically just pan sauce by a different name: fond deglazed and extracted with stock, then thickened with flour. The first time I tried to make gravy without any pan drippings (it’ll be fine, I said, there’s plenty of flavor in the stock) I was greeted with slightly gelled stock – after that experience, I became an obsessive, an evangelist, for deglazing pan drippings. Sometimes, for flavor insurance on Thanksgiving or another big, roasted-meat meal, I roast a few pounds of chicken drumsticks (or wings, backs, whatever I can get) to make extra food. They are the worst, most dried-out and leathery drum-sticks you’ll have the displeasure of trying, because when they start getting hot in the oven, I stab them all over with the tip of a knife (just like you’re not supposed to do) to make sure there are lots of channels for the juices to run out. I roast them deeply, squeezing and poking them while I turn them. When I’m done, I have roasty bones and meat I can use for stock and, more important, puddles of golden-brown, sticky fond stuck to the pan I roasted them in. Then it’s just a matter of pouring in some water, dissolving the fond, and reducing it in a saucepan a little to make sure it isn’t too diluted. Scrape it into a small container, and I have about 8 ounces of pure poultry gold, immaculate eighteenth-century osmazome (see page 83), ready to turbocharge gravy (or any savory sauce or braise, pot of beans, etc.) with rich, mouth-filling, roasted-umami flavor.

Reprinted from Flavorama by arrangement with Harvest, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2024, Arielle Johnson.

Categories

- All Posts (6940)

- Antipasto (2135)

- Author Articles (247)

- Book News (935)

- Cookbook Giveaways (983)

- Cookbook Lovers (257)

- Cooking Tips (109)

- Culinary News (299)

- Food Biz People (552)

- Food Online (791)

- Holidays & Celebrations (272)

- New Cookbooks (149)

- Recipes (1500)

- Shelf Life With Susie (231)

- What's New on EYB (133)

Archives

Latest Comments

- Atroyer7 on Danube Cookbook Review and Giveaway

- demomcook on What foods do you look forward to the most for each season?

- demomcook on Danube Cookbook Review and Giveaway

- Darcie on How cookbooks can help build resilience

- mholson3 on Danube Cookbook Review and Giveaway

- Rinshin on How cookbooks can help build resilience

- sarahawker on Danube Cookbook Review and Giveaway

- Sand9 on Danube Cookbook Review and Giveaway

- hankintoby29 on Heritage Cookies of the Mediterranean World – Cookbook Giveaway

- WBB613 on Feasts of Good Fortune Cookbook Giveaway