The Perfect Instruction

October 20, 2014 by SusieSo, over my years as a cookbook reviewer, I’ve come to realize

there is actually a word formula for the kind of recipe that works

for me.

The ingredients list doesn’t matter that much – unless there’s a

bunch of callouts in the list, like “Saba vinaigrette (see p. 289)”

and “48-hour croutons (see p. 311-313)”.

No, for me, what makes or breaks a recipe is the way the instructions are written. What I like to see looks like this, in what I will call, for lack of a better term, Mad Libs form:

“[ACTIVE VERB] [INGREDIENT] [ADVERB] over [TEMPERATURE], for about [X-Y MINUTES], until [VIVID VISUAL DESCRIPTION]. You should [SEE/HEAR/SMELL/FEEL] [DETAIL] [“-ing” VERB].”

I’ll make up an example:

“Sweat the shallots and shiitakes gently over very low heat, for about 4-5 minutes, until the shallots give up their rigidity and the mushrooms start to curl a bit on the edges. You should hear the mixture start to hiss a little as it begins to dry out.”

Sometimes it’s not exactly that

formula. But I know it when I see it. Here, for

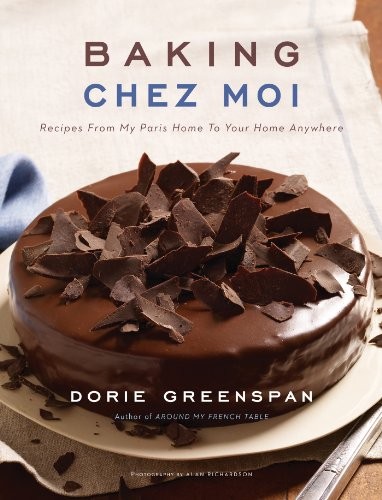

example, are several examples from Dorie Greenspan’s new Baking Chez Moi: “As the bubbles grow

big, be on the lookout for the sugar to start changing color around

the edges.” Or “You’ll think that there isn’t enough

liquid to coat all the dry ingredients, but keep stirring…”

Or “Don’t be discouraged if the mixture curdles; it

will be fine as soon as you add the flour.”

Sometimes it’s not exactly that

formula. But I know it when I see it. Here, for

example, are several examples from Dorie Greenspan’s new Baking Chez Moi: “As the bubbles grow

big, be on the lookout for the sugar to start changing color around

the edges.” Or “You’ll think that there isn’t enough

liquid to coat all the dry ingredients, but keep stirring…”

Or “Don’t be discouraged if the mixture curdles; it

will be fine as soon as you add the flour.”

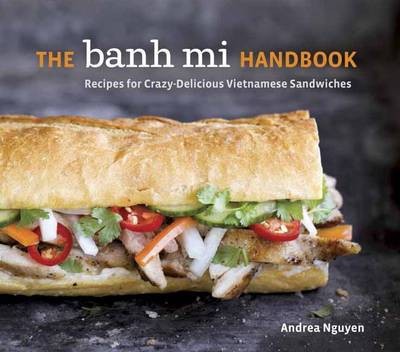

Even a little single-subject

book can be a giant in the details department. In The Banh Mi Handbook, Andrea Nguyen keeps track

of the small stuff with both eyes and nose: “Add the pepper

and sugar, then grind to a fragrant, sandy mixture.” And – I

love this one about portobellos – “Steam will shoot from under the

caps as they cook gill sides down.”

Even a little single-subject

book can be a giant in the details department. In The Banh Mi Handbook, Andrea Nguyen keeps track

of the small stuff with both eyes and nose: “Add the pepper

and sugar, then grind to a fragrant, sandy mixture.” And – I

love this one about portobellos – “Steam will shoot from under the

caps as they cook gill sides down.”

We talked a couple weeks ago about the way some authors make you use your judgement, with subjective terms like “squidgy” and “dollop”. Sometimes I enjoy that too. But by and large, I like my hand held. It can make for a wordier recipe, but I always feel like I’m in good hands when someone’s watching out for the tiniest signs and symptoms. It forces me to pay attention too, and, I’m pretty sure, that makes me a better cook and a better writer, too.

Categories

- All Posts (6940)

- Antipasto (2135)

- Author Articles (247)

- Book News (935)

- Cookbook Giveaways (983)

- Cookbook Lovers (257)

- Cooking Tips (109)

- Culinary News (299)

- Food Biz People (552)

- Food Online (791)

- Holidays & Celebrations (272)

- New Cookbooks (149)

- Recipes (1500)

- Shelf Life With Susie (231)

- What's New on EYB (133)

Archives

Latest Comments

- Atroyer7 on Danube Cookbook Review and Giveaway

- demomcook on What foods do you look forward to the most for each season?

- demomcook on Danube Cookbook Review and Giveaway

- Darcie on How cookbooks can help build resilience

- mholson3 on Danube Cookbook Review and Giveaway

- Rinshin on How cookbooks can help build resilience

- sarahawker on Danube Cookbook Review and Giveaway

- Sand9 on Danube Cookbook Review and Giveaway

- hankintoby29 on Heritage Cookies of the Mediterranean World – Cookbook Giveaway

- WBB613 on Feasts of Good Fortune Cookbook Giveaway