Joan Nathan

March 17, 2011 by JaneJoan Nathan talks about how she unearths the stories she includes her books.

The question I am most frequently asked is, “how do you find all the people with their stories for your books?” And secondly, “how do you get the recipes?” I answer that writing a cookbook is like going fishing. Sometimes you find nothing. Sometimes you reel in a big fish. And you have to take risks. I often feel like Sherlock Holmes when I am sleuthing after a recipe or a good culinary story.

For instance, I was once in Strasbourg eating white asparagus with a French couple at their home. I told them the story of a Dr. Camille Dreyfus who invited me to his home in Paris when I was young and taught me to eat asparagus the proper way, with your fingers. The gentleman with whom I was eating told me that this doctor, amazingly, was his late uncle.

It seems to me that if one is very focused and very interested in other people’s stories, one can find anything. We are so often (more so today than ever) locked in our own little worlds, either with the computer or our Blackberries, that we forget what is outside or right under our nose.

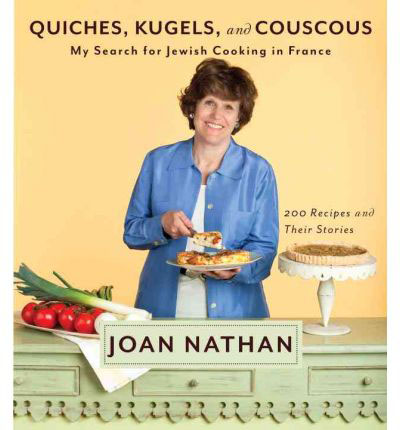

So what is my technique? When I tackle a subject like that of my latest book, Quiches, Kugels, and Couscous: My Search for Jewish Cooking in France, I first ponder the subject. For this book I put together a file on each of the regions of France filled with suggestions of people to interview and recipes to try. By looking through novels and talking with French relatives and friends, as well as French people at the embassies and universities, I spent months filling the file before I even ventured to France.

Speaking the language is also essential to really understanding the mentality of a country. The knowledge that a person has taken the time to learn a language makes communication more direct and enables local cooks to feel much more comfortable with you. There is no question in my mind that language is nuanced. The French, for example, are much more reserved, in general, than Americans. Even if you speak French. I try to respect that reserve and move on.

Having someone act as an intermediary also helps. When I was in Bordeaux at a Sabbath dinner, for example, I tasted a delicious hallah with anise seeds in it. None of the guests assembled thought the home baker who made the bread would share the recipe with me. They said “non, non, non.” I asked the host of the dinner to call and two days later I climbed up 5 flights to the woman’s apartment to learn to make her delicious bread. And, while making the bread, she told me stories about her life.

Although sometimes I have been able to interview a person right off the street, it is rare. And I do not call cold. Most of the time, I have someone make an introduction for me. Somehow people feel safer that way, especially ushering strangers into their house and for me, more importantly, their kitchen!

Yet no matter how perfectly you orchestrate an interview – I know a cookbook author who sets up every interview before she gets to a country – most people and most countries are not that structured. In Israel, for example, even if I call weeks in advance, people will tell me to simply call when I get there. Often when I make that call they have totally forgotten about the date. Since my time abroad is valuable, I try to set up interviews ahead by email or phone and still have lots of juggling to do when I arrive in the country. I also make extra time for the unexpected!

Since France is a café society, I often met with people first at a café so they could size me up. Then if I passed muster, they would invite me to their home and, even better, into their kitchen to cook with them.

Entering someone’s home means being able to gather oral gastronomic history. I am always struck with how few pictures were taken in the past of family meals. Did you ever go through old photos and see how few there are of you and your family at the table, the place we gather three times a day? We food writers are filling a historical void, not only of recipes, but of family food folklore and just plain social gatherings. Our food gatherings tell us who we are and this is what I try so hard to do in my books.

So when people ask “How do you do it?” I often think that anyone who put his or her mind to it could uncover whatever she wanted.

And then I might feel my work was really beshert, Yiddish for coincidences that are meant to be.

Categories

- All Posts (6940)

- Antipasto (2135)

- Author Articles (247)

- Book News (935)

- Cookbook Giveaways (983)

- Cookbook Lovers (257)

- Cooking Tips (109)

- Culinary News (299)

- Food Biz People (552)

- Food Online (791)

- Holidays & Celebrations (272)

- New Cookbooks (149)

- Recipes (1500)

- Shelf Life With Susie (231)

- What's New on EYB (133)

Archives

Latest Comments

- ccav on Food news antipasto

- ccav on What foods do you look forward to the most for each season?

- ccav on Danube Cookbook Review and Giveaway

- hibeez on How cookbooks can help build resilience

- Pamsy on What foods do you look forward to the most for each season?

- Pamsy on How cookbooks can help build resilience

- DarcyVaughn on Danube Cookbook Review and Giveaway

- hettar7 on JoyFull – Cookbook Review & Giveaway

- eliza on What foods do you look forward to the most for each season?

- kmwyman on Rooza by Nadiya Hussain – Cookbook Review and Giveaway